Originally published on Cycling Tips, RIP

In mid-September, British writer Tom Owen, his mate Ben, and photographer Matt Grayson flew over to Spain for a week-long bikepacking adventure. Inspired by one of the 20th century’s greatest authors, the journey produced no shortage of memorable moments, both on the bike and off. What follows is a series of four vignettes from the trip, as told by Tom, with photos from Matt.

PROLOGUE

Ernest Hemingway called Spain “the last good country left”. When we plotted a bikepacking trip there, we decided to take a route connecting places significant in the author’s life. What would we discover on our adventure? Is Spain still good? Is inland Iberia really all dust and rocks and abandoned building projects? How much vino tinto is just enough to get you to sleep at night on a bed of damp grass and twigs?

Hemingway lived in and wrote about Spain as a place he loved. He showed more affection for it than he ever did to the United States of his birth, setting some of his most important books in Spain. But what did he like so much about it?

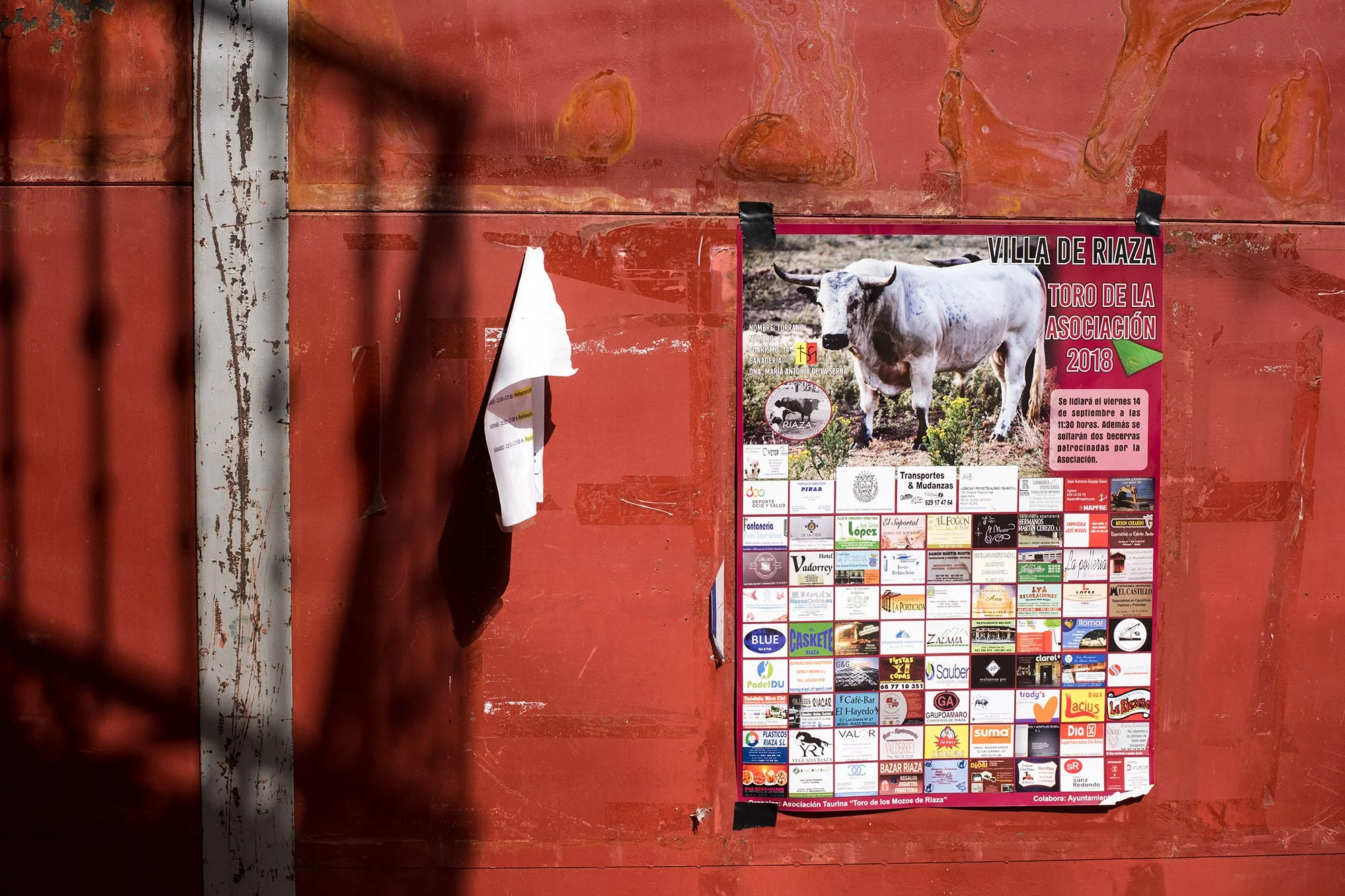

Perhaps he enjoyed being a celebrated foreigner – there is still a plaque in Pamplona that testifies to him being a connoisseur of bullfighting – or was it simply the animalistic, barbarous nature of the corridas themselves? There was certainly something about the rawness of Spain that spoke to him – its frontier-like character, at odds with its proximity to the heart of Europe.

We went in search of the soul of Spain. These are the people and the stories we found.

1. Resurrection on the road to Najera

Have you ever seen someone come back from the dead? I have. When Ben’s tubeless tyre gave up the ghost, unresponsive to even a spare tube and conversion back to running regular tubed. Something was dead inside the wheel, twisted beyond all normal function. We tried and tried, with two different tubes. Nothing could bring the damned thing back. Ben was dead in the water.

With 25km to go until the next town, Najera, and with all the shops shuttered and not a soul in sight, we had no choice but to roll it in on the rim.

Twenty-five kilometres at less than 15kph under the baking noonday sun. A joyous prospect.

As we trundled along in the brutal heat, Ben said to me, “You know, if we can flag down a van or something big enough to take my bike, that might be the best way for me to get to a bike shop.” I had already searched for the nearest ones on my phone — they were both 60km away, on roads turning either left or right at Najera. “Sure,” I said, not feeling particularly sure there’d be anyone along to pick us up.

And then of course there came a van. The first car we’d seen since getting rolling. From the image on the van’s side, it looked like a father-and-son tiling or plumbing company. We flagged it down with emphatic waves. A confused Spanish face with a bushy moustache turned to face me.

I engaged my superpower: Shit But Obsequious Spanish.

“Sirs, we need of you your help. My friend. The wheel of him. It does not function.”

“There is a small town in a few kilometres, you could take him there.”

“Thank you sir, but perhaps you can take him in your large car [I didn’t know the word for ‘van’, still don’t] and to a bicycle shop?”

A hesitation.

“Where are you going, sirs?” I ask, imploring.

“Santo Domingo de Calzada.”

“That is VERY GOOD. It is perfect. There is a bicycle shop there.”

“But it is very far away.”

“That is well. That is well. It is not a problem. May we place the bike in your large car?”

“… Si.”

“Many thanks. The most thanks, sirs!”

And that is how two Spanish tilers brought my friend back from the dead. They drove him to ‘the bike shop’, which turned out to be a workshop for repairing mopeds, but in a town that also boasted a more traditional vendor of pedal-powered conveyances. One new tyre and a couple of backup tubes later and Ben was ready to ride the remaining 20km to meet us in Haro. He beat us there by about 15 minutes.

I later learned that Santo Domingo de Calzada was canonised for his dedication to helping weary pilgrims on the Saint James Way. If you look about hard enough in Spain, there is always a bit of religious coincidence relevant to your current situation.

2. The Grandparents / Los Abuelos

Our daily routes are fluid. Every day there is the ‘if it all goes badly’ finish point, the ‘we really ought to make it this far’ finish point, and an ‘anything past here is a bonus’ finish point.

On Ben’s birthday, we make it to the middle one, but haven’t the light or strength to go further. Montenegro de Cameros has no bar, no restaurant, and no small store to buy anything. We will sleep on the grassy verge just on the edge of town, dine on packets of pre-cooked rice, with some chunks of cheese and sausage for flavour. A decent enough menu, but what would make the evening more pleasant is a bottle of red wine.

As the Spanish speaker, I am dispatched to roll down the hill into the town in search of booze. I quickly find a cluster of elderly Spanish people. They are sitting in the shade, having a natter. Putting the world to rights. Shooting the shit.

I ask them if there is a bar in the town. Yes, they say, but it is closed. It doesn’t help that they all say similar things at the same time in thick rural accents. Some of them lack a full complement of teeth.

I explain about my friend, how it is his birthday, and how we would like to buy a little wine. There is a bar seven kilometres down the hill (in the wrong direction), they tell me. More old people are appearing all the time. They sit down on the long bench facing me and add their thoughts, opinions to the maelstrom. Either a very late-running bus is about to arrive, or I have become the evening’s entertainment.

“Where are you going?”

“You will not get to Viniegra tonight!”

“The bar is just a few kilometres and all downhill.”

“There is no wine here! No bar.”

“There is a bar here. It is closed.”

All of this is mixed in with barrages of Spanish I do not comprehend.

Another elderly gent arrives, gets the situation from one of the originals, then makes a remark in a deep, throaty accent impenetrable to me. It gets a huge laugh. I have been mugged off.

After a bit more of this, I sidle off back to the camp. We sleep well, despite the lack of wine. Perhaps three cars go past our spot between dusk and departure the next day. The biggest nuisance is a particularly insistent cow trying to find its buddy.

I’m struck by this town and how it’s typical of Spain in the modern era. Forgotten rural places that are inarguably, stunningly beautiful, yet deserted. It was the same story in many of the small towns we visited. Only the old remain and not even enough of them to keep a bar in business.

“Brain drain” is an immense, intractable problem for Spain. What young Spaniard would stay in Montenegro de Cameros with Madrid and Barcelona and Bilbao and Zaragoza all beckoning? In the last census there were 99 residents of the village. How long before that figure dwindles to zero?

Sure, there’ll always be a steady trade in selling tumbledown farmhouses to wide-eyed, freshly retired British expats – but that’s only putting off the problem a few years. And besides, we Brits mainly move to rural Spain to get away from each other. Who’d want to live in a ramshackle Spanish pueblo packed to the gills with tax-averse gammon?

3. The most beautiful waitress in the world / La camarerisima

When a duckling breaks from its egg it will imprint on the first living creature it sees. This being becomes ‘mother’ to the little duck, and the bond is extremely hard to break. In much the same way, knackered cyclists will ‘imprint’ on the first waitress (or waiter) who is nice to them, falling hopelessly in love with anyone prepared to bring them fried potatoes in return for money.

And this is how I came to fall (briefly) in love with a waitress in the Navarran town of Agoitz.

In the sparse shade of the bar patio, we stare uncomprehendingly at a menu of snacks. The kind, patient waitress serving us has to come back three times because we can’t decide what we’d like. Eventually we choose, mainly at random.

“I speak English, too, you know,” she replies to my halting order.

“I love you, marry me,” I want to say, before instead ordering three Cokes and two beers.

As my new soulmate leaves, a huge party arrives. They pull up in a coach, tottering toward the bar in wedding gear. First there’s 10, then 20, then all of a sudden we three zombies are awash in a sea of life and colour. There are at least three men with mullets and much good-natured yelling.

We chomp our way through a gigantic salad, a hefty portion of fried potatoes, and glug down the sodas and cerveza. All the while we’re transfixed by these enervated butterflies – do they not feel the heat? Or do they just choose to ignore it?

Exhausted by it all, by the kilometres ridden and the thought of those to come, we retire to doze in the park as the wedding party is called down into the lower garden of the bar for dinner. We hear the party really begin as we remount our bikes – onto the next love affair.

Throughout the trip we’re constantly moving through these communities, a dusty and dishevelled point of contrast to the animated exchanges all around us. There’s the Sunday morning meeting of minds in a Basque cafe/bar attached to the town petrol station, where deep, throaty-voiced farmers exchange jokes and anecdotes while we huddle in the corner charging phones and demolishing glazed donuts.

Or the grill restaurant we fall into with five minutes to spare before the kitchen closes, where a glass of Rioja costs €1.40 and the barman amusedly endures my attempts to order three steaks all at varying points between well-done, medium and rare – despite me confusing the words for “cooked” (“cocido”) and “kitchen” (“cocino”).

“One is most kitchen. One is before most kitchen. The last one, not-most kitchen.”

Spanish people believe in life. They enthuse, strop, laugh, gesticulate, in heat that would reduce the English to gooey, unresponsive puddles on the floor. Has reduced them. They tend toward indulgence, rather than impatience. If you speak crap Spanish to them, as I often did, they help, coax, prod and suggest you towards a comprehensible sentence – rather than forcing you to abandon the project by switching to English immediately. Above all else they are kind.

I suppose that’s why they’re so easy to fall in love with.

4. Pine and lake / The Lumberjack / El Leñador

Hemingway loved Spain’s cities and its wild interior, not the scorched beaches and sangria for which it’s perhaps now best known.

The day before we begin cycling, I visit the Prado, the art gallery in Madrid so beloved by Hemingway that he described the entire city thus: “If it had nothing else than the Prado it would be worth spending a month in every spring.”

To my uneducated eye, the Prado on a Sunday morning was just another art gallery packed with tourists – the looming Goya canvases, impressive, but obscured by baseball-hatted heads and selfie sticks.

Striking out west from Madrid the next day, we tumble off the plateau on which the city sits and bomb down briefly, cross the Guadarrama river, then begin to climb again to the monastery at El Escorial. Of all the places we visit with a link to old ‘Papa’, this is maybe the most poignant.

Hemingway came here on his final visit to Spain, and described it to his friend, A.E. Hotchner, by saying: “I always feel good here, like I’ve gone to heaven under the best auspices.” He was dead by his own hand less than two years later.

The Sierra Guadarrama, too, abounds with significance. The mountain range directly north of Madrid is the setting for For Whom The Bell Tolls. It is less wild as we ride through than when Hemingway had his band of guerrillas surviving, plotting the bombing of a bridge here in the middle of the Spanish Civil War. The summit at Navacerrada is now home to a ghost town ski-resort – laid low by a lack of snow in the last few years. Wild Spain is already reclaiming the space – weeds grow through floorboards, thorny bushes infringe on driveways, and a few cows wander perplexedly amid the tumbledown chalets.

It’s once you reach the logging roads that you truly see what Hemingway loved. The vast green swathes of forestry reserve, navigated by a single winding strip of tarmac. The only other people, lumberjacks, operate frightening machinery with multiple spinning saws – mechanised gauntlets that shimmy up and down the trunk and cut logs of perfect length every time.

Each turn we make takes us deeper into the woods and all the while we’re climbing up and up. Before we crest the final rise, the land falls away to the left – it’s as if a carpet is unrolling down and away. All is green, with no manmade structure in sight. Just one unbroken line to the horizon. The country looks more and more like the great vastness of Montana, or Idaho where Hemingway chose to die.

When we do crest the hill and tumble over the other side, it’s almost all downhill to the promised pre-prandial wild swim, amid the ruined walls of an old sawmill. An unexpected short gravel climb stands in the way of our afternoon dip, but the water down on the other side is worth it.

This is the untamed isolation evoked by the Hemingway name. Not another person in sight. A derelict mill consumed by the lake, mountains looming in the distance. The silence of the deserted promontory.

Epilogue

We went in search of the soul of Spain, but what did we find?

Uninterrupted natural wonder, from the dusty lowlands, to the sometimes snow-tipped peaks of the sierra, to neverending pine forests extending in every direction. We swam in the Irati river in which Hemingway loved to fish for trout, and which flows down from the Pyrenees. We baked under the sun of Navarra, riding past thousands of crops – lettuce, pimentos, watermelon – unimaginable in the wet and dreary climate of the UK. We weaved among the vine fields of La Rioja, and past the bodega where Hemingway got drunk and trapped in the cellar.

We found a nation that is struggling to grow; out from the shadow of fascism for less than 45 years and reeling from the body blows of global recession, while resisting the forces from within that might rend it further apart. The scars of Spain’s recent history aren’t to be seen in its cities, but rather in the countryside – where towns and villages slowly die and the only ‘shop’ is the man with a van who turns up every Tuesday from 11-1pm. Communities have been gutted as their young take flight, with nobody coming to replace them.

We found unfailingly kind and patient people. Spain is the land of ‘the courtesy beep’, the use of the car horn to alert a cyclist you are about to pass them, before swinging your automobile entirely into the opposite lane and sliding by with more than two car widths between. It is a paradise for bike riding. We found help when we needed it and encountered amusement more than impatience.

Did we find a good country? A great one.